Motuo Hydropower Station; what it could mean downstream

- Mattias Burnier

- Aug 28, 2025

- 9 min read

Following the announcement of the Motuo (Medog) Hydropower Station commencing construction, it faces to be the largest dam in the world, but also one with many controversies. Planned to be a steppingstone into China’s new ‘Green Era’, it will provide solutions to many of its energy demands without directly increasing emissions. However, many speculations arise with its construction, and international powers like India are concerned about what it could mean for them downstream. The Motuo Station would provide a geopolitical foothold on the region when completed and destabilise the already troubled border further. What is certain is that China will relent until it is complete, and only then will we discover the true power China will hold.

In human history, there are few moments that truly defined our species; that shaped our modern world from thousands of years back. Most would comment on the invention of the wheel, or, rather more crudely, the discovery of fire, or the agricultural revolution. All of which, yes, have shaped how we survive and advance – however none more than water.

As negligible as it may be, water – the control of water – has been the single largest factor to decimate or multiply civilizations. No other single resource held such a chokehold on both ancient civilizations and modern ones – to the point where the earliest recorded war had set a recurring pattern for the most fought over resource on earth.

It’s difficult to imagine what extent rulers would go to preserve and control this resource, however some of their efforts can be seen. Take aqueducts from the Roman Empire as a simple example; towering structures made of hundreds of arches of thousands of tonnes of stone each individually cut, transported and placed. As gargantuan as the efforts are to preserve and control water, there are mirrored pursuits to destroy it.

During the second punic war at the battle of Cannae of 216 BCE, Hannabal was able to use his positioning near the Aufidus River to threaten Roman supply, ultimately taking victory. His knowledge of the Aufidus and its vital importance to the Roman Legions as their only plausible water source had clamped them in wait for Hannibal’s army. Where at one point, the Carthaginians slaughtered 50,000-70,000 Romans in a day. Crucially, Hannibal didn’t fight for the water – he controlled it – used it as a strategic lever to weaken the Romans before his assault.

From this and countless other examples throughout human existence, it is clear to see the dystopic reality of ‘who controls the water, controls the land’. And this has only been proven to be true in our modern world.

“The yellow river is to China what the Nile is to Egypt – the cradle of its civilization”

-Tim Marshall, Prisoners of Geography

In the early formation of China, the Han had realised, just as many in the region, the importance of waterways to their agrarian civilization, and in the 5th century CE, the Grand Canal linked the Yellow River to the Yangtze. It took millions of slaves to construct this waterway – but had paved China’s rich history and unequivocal skill of hydraulic control and manipulation.

Today, China stands as an emblem of civil engineering where again and again, impossible feats are shown to the world – but seem so unremarkable to the Chinese themselves, saturated almost. The Motuo Hydropower station, however, pledges to be different. Not far down the list of its specifications can you witness the impalpable numbers it will deliver; within, giving a view into China’s true thirst for power.

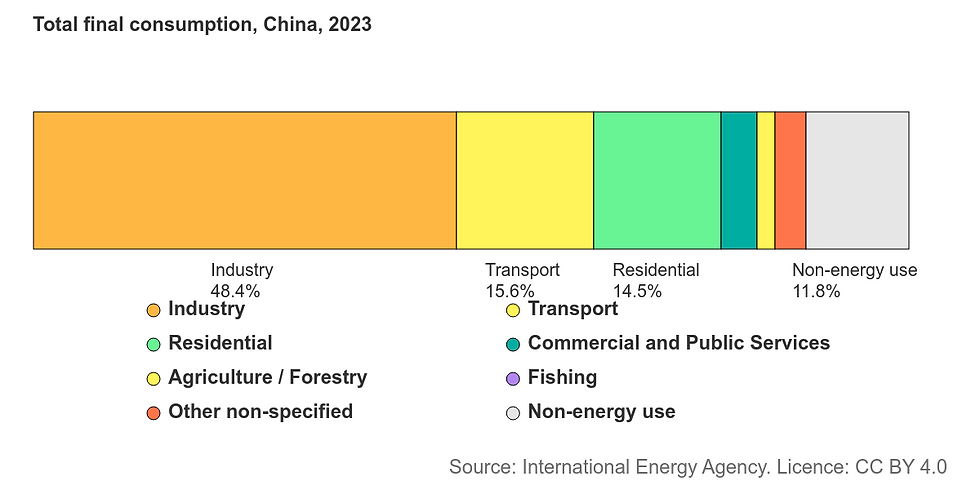

With China’s energy production being the highest in the world, at 9,547 terawatt-hours in 2023, and with 78.5% of its consumption in industry, transport and its residents - it begs the question: how far has the largest electricity consumer already gone, and how far is it willing to go, to supply its citizens, and most crucially, its industrial powerhouse with the energy it demands? The Motuo Hydropower station is certainly an answer to this increasingly foreboding question.

However, looking back only a few years, China found itself in a similar situation - the need for enormous quantities of power. During the booming economic years of 1978-1997, China found its GDP sustaining ~10% growth annually consistently fueling industry potential. Which naturally ate up masses of power and resources that China had been producing from coal power plants. To meet this surge in demand, the Chinese had brought back an old proposition for a hydropower dam - The Three Gorges Dam. The Motuo’s predecessor made a name for itself during its planning and indisputably after its construction in 2012 – after 20 years.

The Three Gorges Dam was so ground breaking that it was most commonly referred to as the dam that changed Earth’s rotation - because it did. Being by far the largest dam constructed and operated, The Three Gorges Dam held such a colossal volume of water that it had subtly altered the distribution of Earth's mass, causing a slight slowing of the planet’s rotation by 0.06 microseconds, a number not seen as significant, but large enough to register.

Despite attempting to be a solution to the power problem, Three Gorges Dam paradoxically only led to increased demand. As a solution, the plans for the Motuo Hydropower stations were quickly and secretly conceived. What was shocking however was China’s commitment to it, but also its unrelenting promise to building bigger and larger - where the Chinese plan to once again build the largest dam in the world, far surpassing the Three Gorges dam.

Month by month the $170 Billion 'gigaproject' seems increasingly more tangible where on July 19, 2025, the primary state owned developer: China Huaneng Co., Ltd., broke ground on the project. The Motuo station is estimated to have a 60 GW capacity and projected to produce 300 Billion kWh of power, completely dwarfing the ostensibly modest 22.5 GW power output of the Three Gorges Dam.

With this in mind, China is accelerating the process. Projected, albeit optimistically, to reach completion by 2033 China seems to have answered its persistent issue of power and reaching President Xi Jinping’s ultimate goal: called “xidiandongsong”, or “sending western electricity eastwards”, and put any future concerns to rest - with only construction work in its path to energy security. However there might be more issues along this path than forethought.

"The Nile flows through millennia of life and history, yet a single dam upstream now holds the power to reshape Egypt’s future.”

The Motuo Hydropower stations will be located on the Eastern rim of the Tibetan Plateau, in the lower reaches of the Yarlung Tsangop river, on a section named ‘The Great Bend’. The Great Bend was chosen as the station’s location because of one crucial reason: In 50 kilometres, the river plummets 2,000 meters in altitude - creating enormous rapids that could be harnessed into power. However, The Great Bend, located uncomfortably near the Indian border in the semi-disputed region of Arunachal Pradesh, proves to be a point of great contention - particularly so because of the planned Motuo Hydropower Station.

In 1950 China annexed Tibet and incorporation was complete in 1951. Before, the Chinese tried numerous times to have some sort of influence over Tibet and their population - and now that they do - they ensure enforcement and, mostly forceful, cooperation from locals. But why invest so much money, effort, and lives into Tibet, and why the constant, choking hammer to keep it in its tight fist.

The China-India border is much more like the Tibet-India border, and China’s oldest fear was Indian advance into Tibet. If this were to have happened, the Indians would have complete manipulation of the Tibetan Plateau, hence, manipulation of three of China’s great rivers: The Yellow, Yangtze and Mekong. Parallel to Hannibal’s victory, China’s concern was not that the Indians would shut off their water, just that they wielded the power to do so. But, with China’s unquestionable presence and supremacy in Tibet, it threatens to commit what it most feared.

The Yarlung Tsangop river, where the Motuo Hydropower Station sits, runs directly south into India after approximately 25-35km and becomes the Brahmaputra River. It flows through India’s Arunachal Pradesh and Assam states, as well as Bangladesh, where it feeds into the Siang, Brahmaputra, and Jamuna rivers. Given India and China’s contentious prerequisite relationship, a fine line has been drawn for the nations involved on how to proceed diplomatically - especially so with the new imbalance of power.

A 2020 report by the Lowy Institute, an Australian-based think tank, noted that “control over these rivers effectively gives China a chokehold on India’s economy.” This, albeit reversed, is what precisely China had initially feared of India’s control in Tibet - however the Chinese control Tibet, and with the Motuo Hydropower Station, have made their new power clear to countries downstream.

Naturally, this broken threshold of regional power, practically a dominion, has sparked great concern both in India and Bangladesh; commonly referenced in their concern is that the Siang and Brahmaputra could “dry up considerably” once the dam is completed, which could cause ecological disasters. However, more frightening is that the dam could be used as a water bomb, destroying the Siang belt where the Adi tribe and similar groups have land and property. Once more, it is not expected that the Chinese would do such a thing, only that they truly would have the power to do so when they see fit.

To combat the disparity in power, but also under genuine concern for its population’s safety, India recently plans to build a hydropower dam on the Siang River, which could act as a buffer against sudden water releases from China’s dam and prevent flooding. This idea is somewhat implausible to combat the vast volume of water that could be released by the Chinese, however India - and more dependantly Bangladesh - hold no other option on how to combat such an event, especially with its potential to cause devastating human and economic damage. In both senses of restriction and liberation of water, China is able to gain a chokehold on India’s economy that practically stifles it to China’s demand - where they could squeeze numerous inequitable benefits in trade and force India or Bangladesh into submission.

“Wherever irrigation required substantial and centralized control, government representatives monopolized political power and dominated the economy, resulting in an absolutist managerial state.”

— Karl A. Wittfogel, Oriental Despotism (1957)

Although being a major step in decarbonization to fuel China’s insatiable energy demand, the Motuo Hydropower Station is also a clear double edge sword. The Tibetan Plateau underscores China’s ambitions of securing energy independence and solidifying geopolitical leverage over one of Asia’s most important rivers. It is unclear how successful the station will end up being; since the Yarlung Zangbo River is fed by glacial meltwater, causing seasonal fluctuation in the river’s volume and possible unstable power supply. However it cannot be understated the overhauled exploitation that China would have, such that it is plausible that China cares more about the leverage the dam gives over its neighbors than its energy-production potential. In any case however, nations affected must tread extremely carefully on their diplomatic relations with China and secure positive trade agreements; which will prove to be challenging given the existent turbulent interactions with the superpower.

Citations:

Atkins, P. J., et al. Early Urbanization and the Hydraulic Environment. 1 Jan. 1998, p. pp 27-39, www.researchgate.net/publication/271841253_Early_urbanization_and_the_hydraulic_environment.

Butler, Gavin. “China to Build World’s Largest Hydropower Dam in Tibet.” BBC, 27 Dec. 2024, www.bbc.com/news/articles/crmn127kmr4o.

“China’s Economy in 2005 Is Not What It Was in 2000.” Council on Foreign Relations, www.cfr.org/blog/chinas-economy-2005-not-what-it-was-2000.

Deming, David. “The Aqueducts and Water Supply of Ancient Rome.” Groundwater, vol. 58, no. 1, Nov. 2019, pp. 152–61, https://doi.org/10.1111/gwat.12958.

Démurger Sylvie. Development Centre Studies Economic Opening and Growth in China. OECD Publishing, 2000.

FRANCE 24 English. “China Starts Construction on World’s Biggest Hydropower Project in Tibet • FRANCE 24 English.” YouTube, 21 July 2025, www.youtube.com/watch?v=n6DoRRa626w. Accessed 26 Aug. 2025.

Global Energy Monitor. “Motuo Hydroelectric Plant - Global Energy Monitor.” Global Energy Monitor, 24 Apr. 2025, www.gem.wiki/Motuo_hydroelectric_plant?utm_source=chatgpt.com. Accessed 26 Aug. 2025.

Howe, Colleen. “Tibet Quake Highlights Earthquake Risk for Dams on Roof of the World.” Reuters, 13 Jan. 2025, www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/tibet-quake-highlights-earthquake-risk-dams-roof-world-2025-01-10/.

Hunt, Patrick. “Battle of Cannae | Carthage-Rome.” Encyclopædia Britannica, 2019, www.britannica.com/event/Battle-of-Cannae.

IEA. “China - Countries & Regions.” IEA, 2022, www.iea.org/countries/china/energy-mix.

IER. “China Embarks on a New Hydroelectric Project — the World’s Largest.” IER, 31 July 2025, www.instituteforenergyresearch.org/international-issues/china-embarks-on-a-new-hydroelectric-project-the-worlds-largest/.

Kuo, Kaiser. “China’s 40-Year History of Economic Transformation.” World Economic Forum, 19 June 2025, www.weforum.org/stories/2025/06/how-china-got-rich-40-year-history-of-economic-transformation/.

Mega, China’s. “China’s Mega Dam Project Poses Big Risks for Asia’s Grand Canyon.” Yale E360, 2025, e360.yale.edu/features/china-tibet-yarlung-tsangpo-dam-india-water.

Megaprojects. “China Is Building the World’s Largest Dam.” YouTube, 6 Aug. 2025, www.youtube.com/watch?v=L9g8qPm7ePg. Accessed 26 Aug. 2025.

Proctor, Darrell. “China Breaks Ground for World’s Largest Hydropower Station.” POWER Magazine, 23 July 2025, www.powermag.com/china-breaks-ground-for-worlds-largest-hydropower-station/.

Singh, Kuldip. “South China Morning Post.” South China Morning Post, 25 Dec. 2020, www.scmp.com/week-asia/opinion/article/3115341/why-chinas-new-hydropower-project-could-have-security. Accessed 26 Aug. 2025.

Stanway, David. “Why China’s Neighbours Are Worried about Its New Mega-Dam Project.” Reuters, 22 July 2025, www.reuters.com/world/china/why-chinas-neighbours-are-worried-about-its-new-mega-dam-project-2025-07-22/.

The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. “Second Punic War | Carthage and Rome [218 Bce–201 Bce].” Encyclopædia Britannica, 24 July 2014, www.britannica.com/event/Second-Punic-War.

“Three Gorges Dam - History and Controversy of the Three Gorges Dam.” Encyclopedia Britannica, www.britannica.com/topic/Three-Gorges-Dam/History-and-controversy-of-the-Three-Gorges-Dam.

UNESCO World Heritage Centre. “The Grand Canal.” Unesco.org, 2013, whc.unesco.org/en/list/1443/.

Wikipedia Contributors. “Three Gorges Dam.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 22 Mar. 2019, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Three_Gorges_Dam.

Marshall, Tim. Prisoners of Geography : Ten Maps That Tell You Everything You Need to Know about Global Politics. Elliott And Thompson Limited, 2016.

Wittfogel, Karl A. Oriental Despotism : A Comparative Study of Total Power. Yale University Press, 1957.

Comments