Cold War 2.0: Are We Back in a Global Standoff?

- Manuela Medeiros

- Sep 9

- 7 min read

Updated: Sep 17

The Cold War was not fought with bullets, but with ideology, influence, and fear. From 1945 to 1991, the U.S. and USSR clashed for global dominance. What began as an uneasy alliance quickly turned into a struggle that defined the second half of the 20th century... or is it now the 21st?

By: Manuela M.

The Cold War, often described by your fellow history nerds and political enthusiasts as “the closest the world ever came to nuclear annihilation”, was the tense and protracted struggle between the United States and the Soviet Union, lasting from 1945/47 to 1991. Following Nazi Germany's surrender in May of 1945, the wartime alliance between the U.S. and Great Britain faced the USSR, both on different ends of the political spectrum. By 1948, the Soviet Union had installed left-wing governments in eastern European countries that were previously liberated by the Red Army. Britain and The United States both feared the permanent Soviet domination of eastern Europe as its installment would threaten democracies of western Europe. Conversely, the Soviets were determined to maintain their control over eastern Europe to protect themselves from any possibility of a renewed threat from Germany. The USSR's intention was to spread communism worldwide within world revolutions. The Cold War began to fully solidify in 1947-1948 when the United States aided western Europe with the Marshall Plan and the Soviets installed fully openly communist regimes across eastern Europe.

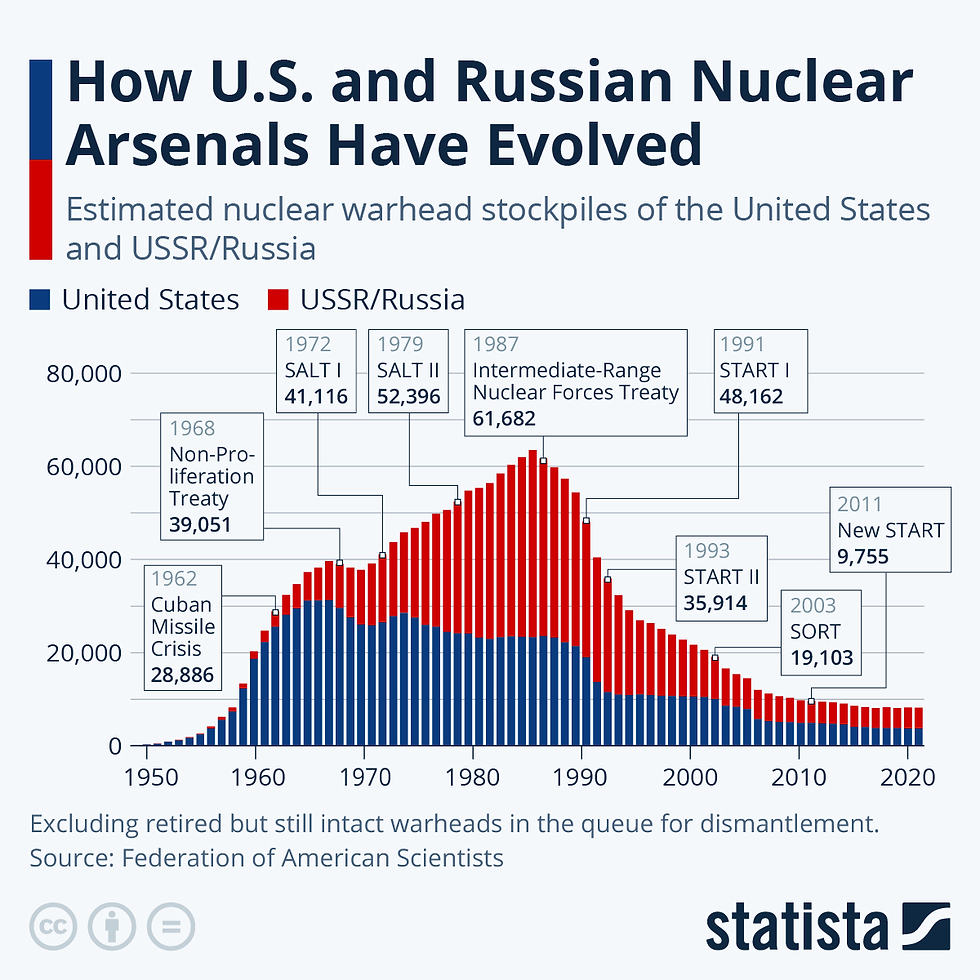

It was the 20th century, nukes and ammos were worth more than any porsche or, what the Soviets would like to call a "глупая дорогая машина"—and proxy wars and arms race were the new pink. But now, in the 21th century, the new pink is economic sanctions and propaganda. Take for instance, the United States (yes, again) and China, subject to a multifaceted competition that reminisce of the U.S.-Soviet rivalry.

The rivalry between the United States and China has become one of the defining features of the 21st century, echoing the high-stakes competition once seen between Washington and Moscow. Cyber espionage, economic sanctions and influence campaigns have transformed this relationship into a multifaceted struggle for global power. According to The Heritage Foundation, the U.S. is now engaged in what can be described as a “new Cold War” with China, one that is more complex, more dangerous, and more deeply intertwined with global systems than the Soviet rivalry ever was. Unlike the USSR, China is embedded within international trade and technological supply chains, giving its competition with the U.S. an added layer of urgency.

But what happens when the world’s two largest powers see competition not as an option, but as destiny?

Well, one major area of concern is military modernization. Over the past two decades, China has rapidly built up its armed forces, investing heavily in advanced missile systems, cyber capabilities, and naval expansion. Heritage analysts warn that this shift threatens to alter the balance of power in the Indo-Pacific and increases the risk of confrontation, particularly around flashpoints like Taiwan.

A different area of competition exists in the technological and economic sectors. The Heritage Foundation points out extensive Chinese cyber activities and intellectual property theft, which have resulted in billions of dollars in annual losses for the U.S. economy. To address this issue, Heritage recommends bolstering domestic supply chains, protecting innovation, and assisting U.S. companies that compete with Chinese firms backed by the state.

Yet this contest is not just military or economic, it is also ideological and strategic. Heritage argues that the U.S. must mobilize its strengths, alliances, democratic stability, and global leadership—to effectively counter Beijing’s ambitions. Their recommendations include boosting deterrence in the Indo-Pacific, achieving greater energy independence, and adopting a whole-of-government strategy that unites political, economic, and security efforts.

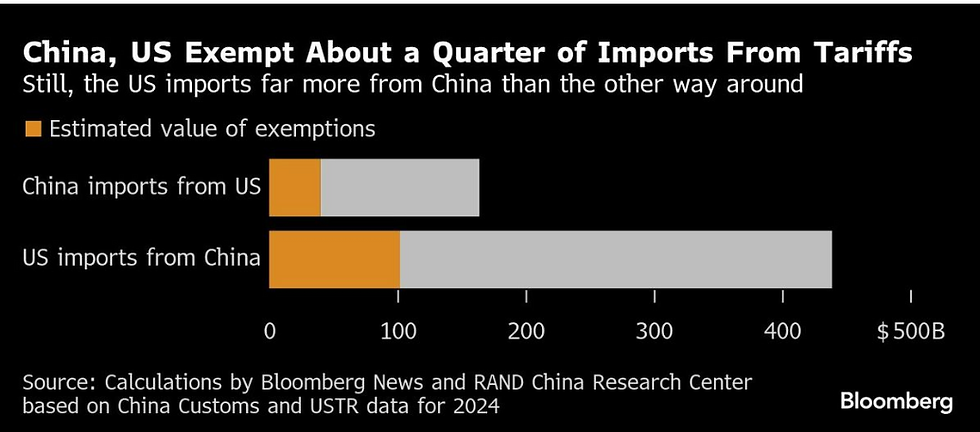

In 2022, despite the ongoing tariff conflict, US-China trade hit a record high of $689 billion. In contrast, during the entire Cold War era of the 1980s, US-Soviet trade totaled less than $50 billion.

Considering this, although trade between China and the US and its allies continues to increase, it is becoming a smaller part of China's overall global trade. In other words, China is increasingly depending on trade with the rest of the world rather than with the US and its allies.

Ultimately, this U.S.–China rivalry is not a repeat of the past but a new era of global competition. Where the Cold War was defined by nuclear standoffs and ideological blocs, today’s confrontation spans everything from cyberspace to shipping lanes. The question, as Heritage frames it, is whether the U.S. can adapt quickly enough to meet the challenge of an adversary deeply embedded in the global order.

Now taking the K3 train from Beijing we arrive at the K19 in Moscow, Russia. Russia? You may ask. Well, yes. The Federation of Russia is a direct product of the end of the Cold War in 1991 and the December 8th Belovezh Agreement; The Federation of Russia was once known as the USSR. Well, the relationship between the U.S. and Russia have deteriorated dramatically, not only during the Cold War, no, especially after Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. What began as a territorial conflict quickly escalated into a geopolitical struggle, with Washington and Moscow once again locked in a contest reminiscent of the Cold War. Just as Vietnam and Afghanistan became battlegrounds for U.S.–Soviet rivalry in the 20th century, Ukraine has emerged as today’s defining proxy war. The U.S. provides Ukraine with military aid, intelligence, and economic support, while Russia frames its war effort as resistance to Western encirclement. This indirect clash allows both sides to exert power without engaging in direct conflict, though the risk of escalation looms large.

Outside of Ukraine, the rivalry extends to other areas. In the Middle East and Africa, both Washington and Moscow have pursued influence via arms deals, mercenary groups, and economic leverage. From Syria, where Russian intervention supported Assad's regime, to Africa's Sahel region, where Russian-backed Wagner forces established a presence, proxy conflicts continue to characterize their competition.

The Times and other observers argue that these proxy struggles reveal the fragility of global order. Instead of open war between the U.S. and Russia, smaller nations bear the cost of great-power competition, often enduring prolonged instability. The Ukraine conflict, however, is far more destabilizing than previous proxy wars, it sits at the heart of Europe, threatening NATO security and global energy supplies.

The Cold War (1947–1991) was defined by a clear bipolar order: the United States led the capitalist, democratic bloc through NATO and global alliances, while the Soviet Union commanded the communist bloc through the Warsaw Pact. Most states aligned themselves with one side, while “non-aligned” countries remained limited in their global influence.

By contrast, today’s geopolitical environment is multipolar. The United States and China are often framed as the two dominant players, but power is no longer concentrated in just two hands. The European Union exerts influence through its economic weight and regulatory power; India is rising as a strategic and demographic giant; regional actors such as Brazil, Turkey, and Iran project influence in their neighborhoods. This dispersion of power creates a fluid international order, where states may cooperate with one great power in one area while opposing them in another (e.g., India’s strategic partnership with the U.S. against China, while also buying oil from Russia).

This multipolarity makes the current era less predictable than the Cold War, as alignments are not rigidly ideological but rather pragmatic, shifting with economic or security interests.

A defining feature of the original Cold War was the sharp economic separation of the two blocs. The Soviet Union maintained a centrally planned economy with minimal integration into global markets, while the United States led a capitalist, market-driven system. Economic relations between the blocs were negligible, so sanctions and embargoes had little mutual cost.

In the modern era, globalization has produced an unprecedented level of economic interdependence. The U.S. and China, despite being strategic competitors, remain deeply tied through trade, technology, and finance. For example:

China is the largest supplier of manufactured goods to the U.S.

The U.S. is a key market for Chinese exports and a major source of investment.

Global supply chains (e.g., semiconductors, rare earth minerals) tie rival economies together in ways that make “decoupling” both costly and complex.

This interdependence acts as a deterrent to direct military confrontation, since war would inflict devastating economic consequences on all sides. However, it also creates new weapons of rivalry: tariffs, sanctions, technology bans, and financial restrictions become tools of strategic competition. Unlike the Cold War, where economic isolation was clear-cut, today’s rivalries are marked by selective decoupling and weaponized interdependence.

Although today’s world is not divided by two ideologically opposed superpowers, Cold War echoes are unmistakable. Great-power rivalry, military buildups, and proxy conflicts remain part of the international landscape. Yet unlike the mid-20th century, rivalry now unfolds in a multipolar, interconnected, and technologically complex world.

The stakes may be higher than ever: nuclear weapons remain, but so too do economic vulnerabilities and technological dependencies that could destabilize the global system. The challenge is to manage competition without sliding into catastrophic conflict.

Diplomacy, international cooperation, and responsible leadership are essential. The Cold War showed that continuous competition without effective communication can drive the world to the brink. In today's context, where conflicts can spread via trade, cyberspace, or information networks, vigilance and dialogue are vital for global security.

And remember kids, a naval "blockade" isn't the same as a naval "quarantine"! One will avoid war and the other will start it.

Sources cited:

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Cold War | Causes, Facts, & Summary.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 19 Jan. 2024, www.britannica.com/event/Cold-War.

JFK Library. “The Cold War.” Jfklibrary.org, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, 22 Oct. 2021, www.jfklibrary.org/learn/about-jfk/jfk-in-history/the-cold-war.

Yu, Miles. “The Dangerous Myth of US-China Cold War Tensions.” Hudson Institute, 14 Mar. 2025, www.hudson.org/foreign-policy/dangerous-myth-us-china-cold-war-tensions-miles-yu.

“The Perils of a Cold War Analogy for Today’s U.S.-China Rivalry.” United States Institute of Peace, 23 June 2025, www.usip.org/publications/2025/06/perils-cold-war-analogy-todays-us-china-rivalry.

“The US Is Already Losing the New Cold War to China.” American Enterprise Institute - AEI, 27 May 2025, www.aei.org/op-eds/the-us-is-already-losing-the-new-cold-war-to-china/.

Abrams, Elliot. “The New Cold War.” Council on Foreign Relations, National Review, 4 Mar. 2022, www.cfr.org/blog/new-cold-war-0.

“The Graphic Truth: US-China: Cold War or Cold Cash? - GZERO Media.” Www.gzeromedia.com, www.gzeromedia.com/living-beyond-borders-articles/graphic-truth-us-china-cold-war-or-cold-cash.

“Belovezh Accords | Encyclopedia.com.” Www.encyclopedia.com, www.encyclopedia.com/history/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/belovezh-accords.

Lüdtke, Lisa. “Mounting Tension in Asia.” GIS Reports, 22 Nov. 2018, www.gisreportsonline.com/r/us-china-tensions/.

Chia, Osmond. How Oil Has Brought China, Russia and India Closer Together. 2 Sept. 2025, www.bbc.com/news/articles/c627p49lp40o.

Some of the measures introduced from both the First and Second New Deal had greater significance than others

Comments