The United States lost the Vietnam War at home, not on the battlefield.

- Manuela Medeiros

- Oct 2, 2025

- 12 min read

By: Manuela Medeiros

Saigon. The land of the captured and the fallen. A monument of communism, capitalism and pseudo-revolutionaries, an emblem of the American flag in the heart of Vietnam. Viewed by many in the West as heroes and by others across the world as imperial villains, the United States couldn’t escape the fate it helped shape.

As President Lyndon B. Johnson remarked: “The ultimate victory will depend on the hearts and minds of the people who actually live out there.”, he appealed to something considerably larger than a military victory, he appealed to the soul of the United States of America, a nation torn between the chaos on domestic soil and a conflict fifteen thousand km away.

How could a superpower with unmatched military strength ever lose a war to such a small, ill-equipped nation on the other side of the globe? The Vietnam War was one of the most barbarous world conflicts in modern American history, resulting in the first clear defeat for the United States military.

The U.S had won battles. But failed to win the war.

From 1955 to 1975, the U.S intervened in Vietnam to prevent the spread of communism in Southeast Asia, as part of its broader Cold War ‘containment’ doctrine and policy. With intensive military operations and firepower, the United States had never suffered a decisive defeat in direct combat, and yet it miserably failed to achieve its strategic goals.

The United States had deployed over half a million troops, conducted decade-long campaigns that cost over 58,000 American lives and stained the nation’s reputation. “The war was not lost in the jungles of Vietnam, but in the living rooms of America — on the night of the Tet Offensive.” hypothesized Christian Appy, a leading historian of this red battle fought within indifference and fear but won with pride and defiance; a victory celebrated in the same soil that once only mourned. A victory fought not only with bullets, but with belief.

This conflict subverts any standard set by American militarism during war—tackled by the unsettling might of guerilla tactics or the unfamiliar terrain; the end point was clear, the U.S. could have never imagined that its terminus would not be in Hanoi, but inside the American mind.

Vietnam shattered the expectations of American militarism. This war was not only against the Viet Cong, it was against American democracy—one defined by uncertainty, protest and distrust. The Viet Cong was fluent in asymmetry, they found beauty in uncertainty and turned it into purpose. The Viet Cong didn’t lack a motive, they fought for what they saw as liberation while the U.S fought for silence; America fought a war it increasingly struggled to justify.

This incongruity has led historians to question not just why the United States failed, but where the war was truly lost: in the jungles of Vietnam, or in the fractured minds of the American people. While military challenges were significantly salient, it was ultimately the collapse of political and public support at home, catalyzed by judicious media coverage, social unrest and unthinkable political decisions, that paved the way towards American failure in Vietnam. Despite its resolute position, a recon of how battlefield realities and strategic oversights fed into domestic collapse, showing that the two fronts were deeply interconnected, is essential.

In the 21st century, a single tweet can mislead or mobilize millions. The 20th century was no different, though instead of tweets, it was photographs; instead of reels, articles. Media has shaped the public for centuries, beginning with the invention of movable-type press by Johannes Gutenberg in the 1440s. In the following decades, the emergence of the radio and television ushered in a new era of mass communication. By the 1960s, these mediums were broadcasting what became known as the “first televised war”: the Vietnam War. From the rice paddies of Southeast Asia to the living rooms of America, the conflict was no longer distant and public perception was altered in media res. The media did not merely report the war; it reframed it.

How could a nation claim victory abroad when it was losing faith at home?

As the media expanded its span of control from America to Vietnam, it began covering other battles and massacres within the war.

A historian might draw on contemporary journalism as a source to outline the public impact of historical events and it was no different during the Vietnam War. Between the lines of the book ‘Embers of War’, a piece of literature exploring the dawn of the Vietnam War, Fredrik Logevall proposes that “The My Lai revelations fundamentally altered public perception —not just of the war, but of the soldiers fighting it.” The My Lai massacre was one of the most significant events of the war, “stripping the war of its last illusions. Americans could no longer tell themselves they were fighting a fair war” writes historian Christian Appy. In March 1968, U.S Army soldiers from Charlie Company brutally murdered over 300 unarmed Vietnamese civilians in the village of My Lai. The victims were young women, children and elderly. The massacre was initially silenced by military command and media control, but in 1969, Seymour Hesh broke the silence; supported by photographs taken by Army photographer Ron Haeberle. As these images were published on the front pages of newspapers across America, public outrage was immediate and visceral. As George Herring notes,“When the photographs of My Lai hit the front pages, they did more than shock: they undermined whatever moral legitimacy the war still had.

The fine grain of detail that the American military attempted to cover up the brutality of this massacre disclosed the reality of militia activity; the U.S was no longer ‘monitoring the situation’, they were no longer just ‘enforcing containment’, they were erasing Vietnam.

The power of journalism in this case did not merely document massacre—it altered the national consciousness. My Lai had instantly become a multinational symbol of a war gone morally adrift, contradicting the American narrative of democratic liberation.

If we examine remotely the causes of media unrest during the war, My Lai is not the sole culprit in this matter. In the same year, the Tet Offensive derailed the American perception of the war; outlining the lack of strategy within U.S militia as the Viet Cong stormed over 100 cities and 70,000 troops took control over the Nation.

After all, the Vietnam flag is red and yellow for a reason.

Despite being a military dereliction for the North, the scale and shock of the attacks stunned the American public and subverted previous claims that the U.S was near victory. Truth was that “he won’t quit no matter how much bombing we do.” When “history doesn’t repeat itself but it sure does rhyme”, Ho Chi Minh had lived through this very war in 1946 and in 1954. McNamara was correct, Minh or the Viet Cong wouldn’t quit. As the credited news anchor Walter Cronkite famously declared that the war would end in stalemate, proposing to President Lyndon B. Johnson, “If I’ve lost Cronkite, I’ve lost Middle America.” This growing “credibility gap” between what officials claimed and what citizens witnessed caused widespread disillusionment.

Following the repercussions in 1968, the media shattered a glass Americans never knew about. The media disproved the American government and paved the way for countless manifestos of spite. Military commitment was now politically unsustainable, the war was lost in Suburbia, not in Saigon.

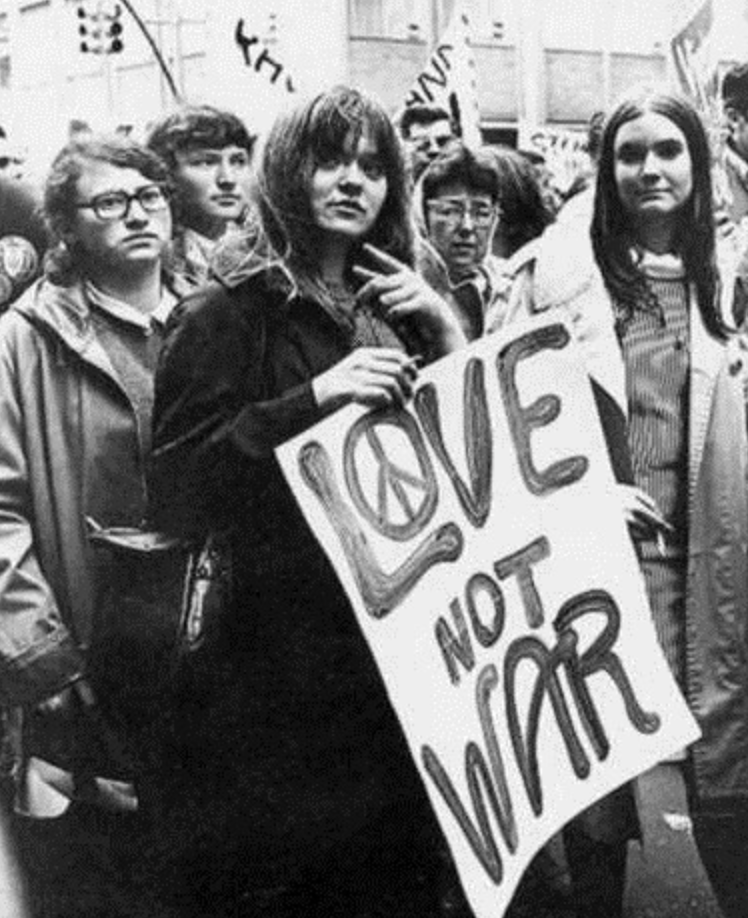

In regards to media coverage, the Vietnam War saw an unprecedented wave of domestic protest. What began as isolated demonstrations by students and intellectuals grew into an unsettling nationwide movement involving veterans, civil rights activists, and even politicians. By the late 1960’s, anti-war protests had become a symbol of American politics. “Make love not war” was now the national anthem of the revolutionary, a battle cry for change.

A common misconception about the Vietnam War and its casualties was that killings were carried solely on Vietnamese soil. Conversely, deaths were recorded miles off the coast of Hanoi—from Saigon to Kent State University, no revolutionary mind was safe. In May 1970, National militia opened fire on student protesters—killing four people and further wounding the divide between American society. Draft resistance became widespread, with 50,000 young men fleeing to Canada or burning their draft cards in public. The movement was beyond anti-war but rather anti-establishment; it changed the moral authenticity of the American foreign policy and raised questions about its democracy, imperialism and racism.

As the political pressure reached the streets of Washington, Lyndon B. Johnson announced in March 1968 that he would not seek re-election. His successor, Richard Nixon, campaigned on the grounds of “peace with honor”, reflecting the public desire to end war. In 1971, the leaked Pentagon Papers confirmed that successive administrations had misled the public of the war’s progress, further polluting anti-war sentiment and mistrust, which aimed at pressuring the government to act against the war.

Twenty years, five presidents and countless policies. Whether it was the erosion of domestic support or the increasing pressure on policymakers, politics and economics during the Vietnam War was in constant metamorphosis.

Whilst 2.3% of the American GDP went directly into the Vietnam War, Urban needs were left unsatisfied and the population lacked access to basic necessities: infrastructure, housing, transportation, education and healthcare. As reform budgets were cut back due to the war emptying the pockets of the American programs. Johnson’s launched 1964-1965 agenda of a “Greater Society”, aiming at addressing poverty, inequality and racism was an ambitious move that rapidly derailed as the Vietnam War escalated; Johnson was left with a moral dilemma and could no longer sponsor such a program and society was frantic about how the government was spending its money.

Congruent to the fluid economy, Nixon’s policy of Vietnamization—the process of steadily transferring combat responsibilities to South Vietnamese forces (ARVN) while withdrawing U.S troops—was not adopted primarily for strategy, but rather for need. The United States was no longer able to validate the cost of war, either in dollars or lives.

Between 1969 and 1973, American troop counts dropped sharply, and by March 1973, the last U.S combat troops had left Vietnam. Signed in January 1973, The Paris Peace Accords were a direct result of internal American pressure rather than battlefield victories. The American public could no longer support the war, and policymakers had no other choice than to find a diplomatic exit.

In 1973, Congress passed the War Powers Act, which was aimed at limiting presidential authority over waging war without congressional approval. This act was mostly passed due to American experience in Vietnam, mimicking the long term political fallout of the conflict—confirming that war had not only divided society but had led to a substantial change in the institutional balance of the United States..

In spite of its main argument, this essay recognizes that military and strategic failures played a crucial role in undermining domestic support. The American military was significantly ill-prepared for the type of guerilla warfare practiced by the North. U.S forces often relied on conventional tactics—from large-scale bombings to search and destroy missions, its ineffectiveness causing tremendous civilian harm.

Their usage of chemical agents such as napalm, Agent Orange, and indiscriminate air strikes alienated the locals, subverting the ultimate American objective of “winning hearts and minds.” The South Vietnamese government, under rigorous leaders, was plagued by corruption, inefficiency and an overwhelming lack of legitimacy. The ARVN forces would lack morale and were heavily dependent on American airpower and logistics. The United States was unaware that the usage of these chemicals polluted their image more than it helped—the United States began to be portrayed as aggressors rather than liberators and its actions ignited an ethical crisis.

Another symbol of American oversight was the Ho Chi Minh trail—an elaborate supply route running through Laos and Cambodia, which allowed the North to sustain their operations regardless of the heavy bombing. In spite of the 1972 Operation Linebacker or the 1965-1968 Operation Rolling Thunder, the United States perpetually failed in cutting off these supplies which allowed the Viet Cong to transport troops, weapons and supplies to the Southern Front whilst representing the Northern resilience at the face of adversity. The Ho Chi Minh trail highlighted how whilst the United States fought for survival, to simply go back home—the VietCong fought with purpose—seeking independence for their home. This psychological bridge between Northern and Southern motive was visible to the American eye and the media was aware of the struggle for morale, summoning crowds to side “with the enemy” due to their inspiring battle call.

While the U.S won countless battles, including against the Tet Offensive, it failed to translate these victories into strategy. This persistent failure contributed to the loss of confidence at home. In this sense, the war was not entirely lost in domestic soil—it was also lost in Vietnam where military strategies were no match to political objectives.

After the policy of Vietnamization concluded the withdrawal of U.S troops from Vietnamese bases, it became clear the extent of Southern dependence on American support. Despite billions of dollars in aid and training, the ARVN proved itself to be unable to resist a major offensive from the Northern militia.

The captured land had fallen in April 1975–Saigon had collapsed; marking the official end of war. North Vietnamese tanks rolled into the capital as helicopters evacuated the last Americans from the American embassy. The drastic images of this moment was a shock to the American prestige.

Most importantly, the United States chose not to return to the conflict—not due to its military capability, but due to its political and public instability. Congress abstained from the authorization of further military aid, and President Gerald Ford accepted that the war was over. The choice not to re-engage in conflict reflected the prevailing impact of domestic opposition. As Henry Kissinger later noted, “We fought a military war; our opponents fought a political one.”

An oversimplified approach towards this conflict would be that the war was only lost at home. In reality, the home front and the battlefield were deeply connected. As military failures flashed the news, public support was made harder to maintain—which consequently limited military options. The war had begun its feedback loop: each battlefield misstep eroded confidence at home, and each domestic protest became a constrained strategy abroad.

When recalling the events that unfolded during the My Lai massacre, that bittersweet connection between the battlefield and home is evident. Events similar to My Lai had a disproportionate impact due to its exposé of the moral cost of the war; amplifying the arguments used by the crowd of anti-war activists.

Similarly, the 1971 Pentagon Papers did not reveal any new battlefield failures—instead, they showed how the government had long believed that the war was unwinnable. This revelation destroyed the credibility of the American government and shattered what was left of public trust—confirming that the issue was not solely military, but rather moral and political as well.

The Vietnam War did not end in 1975–it transformed. Its legacy reverberates through every corridor of American policy and every street where protest once roared. In the decades following Saigon’s fall, the conflict became a cautionary tale for both military commanders and political leaders. The “Vietnam Syndrome”—a national resistance against engaging in foreign conflicts without clear objectives or public support—defining American politics for a generation. Presidents from Reagen to Obama navigated this shadow with caution—in Somalia, Rwanda and Iraq; no longer could a government assume that military strength alone would assure success let alone victory. Public consent had become a strategic necessity. As Secretary of Defense Robert Gates later reflected, “Any future defense secretary who advises the president to again send a big American land army into Asia…should have his head examined.”

According to the saying “a good historian always looks at both sides of the conflict”—to fully grasp the reasons as to why the United States failed in Vietnam, it is crucial to move beyond tactical military analysis and examine the deeper historical forces shaping the war’s trajectory. Vietnam was not simply a Cold War battleground, but the stage upon which America’s post 1945 sense of invincibility met the realities of domestic pressure and unmatched strategy. While traditional, or “orthodox”, historians such as aguentar Lewy have attributed defeat to political and strategic mismanagement in SaigonModern revisionist scholars—including Christian Appy and George Herring—emphasize the critical role of public perception and media scrutiny at the home front. The Vietnam War marked a turning point in U.S military history: for the first time, real time images of violence reached American living rooms, collapsing the distinction between combat zone and civilian space. Gallup polls recorded a 15% drop in support for the war in the weeks following the Tet Offensive. This unequalled visibility morphed war into a public spectacle and into a domestic crisis.In this scenario, the conflict was not lost due to American troops being outperformed, but rather because they failed to uphold moral or political legitimacy with their own population. Placing the war in the broader framework of 20th-century American interventionism, from Korea to Iraq, enables one to see Vietnam not as an anomaly but as a case example. This pattern is reflected in later actions, especially the Gulf War in 1991 and the Iraq War in 2003. While the former was framed as a limited, multilateral response to Iraqi aggression, the latter evolved into a prolonged occupation justified by questionable intelligence and ideological reasons, including the strategic influence of pro-Israel neoconservatives in American foreign policy. Scholars like John Mearsheimer and Stephen Walt argue that Zionist lobbying and U.S. support for Israeli security goals fostered a view of the Middle East that depicted the Iraqi regime as both attractive and inescapable. Vietnam thereby becomes the story held by the United States—a framework for understanding how America's wars, even when engaged with greater military power, can undermine their ideological foundations under global examination.

Ultimately, the Vietnam War was a multifaceted affair—welcoming double entendres in regard to its finale. In the final analysis, the United States lost not because of a battlefield defeat, but because of the political collapse and disillusionment at home. While guerilla tactics, flawed tactics and a resilient opponent contributed to its utter defeat, it was the erosion of domestic support, driven by media exposures, mass protests, and political scandals—that ultimately made it implausible to sustain any war efforts. The Vietnam War reveleaded the limits of military power in the absence of political transparency and public consensus. In this sense, this war was not only a military conflict , but also a battle for the soul of American democracy—and it was lost in the hearts and minds of the American people.

Comments